Latin Beat Magazine, August, 2003 by Luis Tamargo

Once upon a time in Miami, during my first meeting with Jesús Caunedo (alias La Gruya, or "The Crane "), I realized that the nickname applied many moons ago by a bongó-playing bandmate to the tall, gray-haired reedman was well justified, considering his partial resemblance to those large birds with very long legs and necks.

What matters, most of all, is that this extraordinary multi-instrumentalist/ bandleader/composer/arranger has played a vital role in multiple musical events of historical significance.

BORN in Havana in 1934, and regarded as one of the most sought-after Cuban studio musicians of the late 1950s, Caunedo was one of the founding members of the Club Cubano de Jazz and participated in numerous classic Havanese recordings, from Chico O'Farrill/Las D'Aida's unprecedented 1957 collaboration to Omara Portuondo/Julio Gutierrez's Magia Negra to Walfredo de los Reyes Jr.'s landmark Gema debut (Cuban Jazz, 1960).

After leaving his native island in 1960, the author of Guanguajira has made equally notable contributions to the musical environments of the Big Apple and his adopted island.

"Never expect a true musician to completely retire," declared another legendary reedman in exile, Tata Palau, in a recent LATIN BEAT interview. Palau's comment can be applicable, of course, to the subject of the following interrogation.

Currently residing in Carolina, Puerto Rico, Caunedo has been featured in various important recordings conducted in recent times, including but not limited to the Cuban Masters' Grammy-nominated gathering (Los Originales, Pimienta, 2001) and Puerto Rican pianist José Lugo's innovative debut (Piano Con Mata, Bronco, 2003).

LUIS TAMARGO: Were there any other musicians in your family before you came along?

JESUS CAUNEDO: Not really. Since my father was a baker, however, my musical vocation probably had something to do with the panes de flauta that he baked (LAUGHTER). My mother had a good ear for music and she sang beautifully. You could say that I'm a musical product of my native country's pre-Castro public education system: I was raised and learned music at Ceiba del Agua's Instituto Cívico Militar, a tuition-free, vocational boarding school for orphans (My father died when I was 6 years old) in which I was enrolled from that age until I was almost 17. That is where I studied music with Manuel García Gatell, a native of Cienfuegos who went beyond the call of duty and functioned as a second father to me. By the age of 15, I was playing with a band that we organized at the institute. Juvenal Blanco, a professor who was also raised at that school, led it.

LT: Do you have a favorite instrument?

JC: My first instrument was the clarinet, but I enjoy playing all instruments at my disposal. Instruments are like women; each instrument has its own peculiarity, a distinctive swing. Each instrument has a different sonority, a different expressive feeling. So I can't say that I have a particularly favorite instrument.

LT: Is it true that you began your professional career in 1950 as a saxophonist, despite the complaints expressed by Professor García Gatell?

JC: Yes. He wanted me to become a clarinetist, a profession that could have led to hunger and starvation (LAUGHTER). I initiated my career playing sax with the bands led by Otoniel Acosta and Pantaleón "El Cojo" Pérez Prado at dives such as El Palete and La Sierra. Despite the lack of financial rewards, I must confess that I had a wonderful time as a single young man playing in places packed with horny women (LAUGHTER).

LT: When did you acquire the nickname of La Gruya (The Crane)?

JC: Later on, when I was working with Rey Díaz Clavet's band at the C.O.C.O. radio station. The nickname had to do with the story behind a political advertisement utilized during (Fulgencio) Batista's senate race. It alleged that after a crane was accidentally run over in his country estate, he made arrangements for the injured bird to get prosthesis, a wooden leg (LAUGHTER). Right around that time, I fractured my leg while playing soccer and it had to be put in plaster. Therefore, whenever I had to stand up and walk to the microphone at that radio station to playa solo, I had to use a crutch. That's when the bongosero named Lázaro "Manteca" Plá carne up with the nickname, in reference to the previously mentioned political crane ... By the way, I recorded for the first time with Díaz Clavet's orchestra. This recording included the tune titled Al Compás del Chachachá, featuring María Luisa "Pucha" Choréns (Olga Choréns' sister) on vocals.

LT: By 1954, you became a vital component of Rafael Ortega's 4-piece saxophone section ...

JC: It was a very lucrative gig. Ortega was a very good pianist with a very bad temper (LAUGHTER). While playing with his band at the Sans Souci, I had the honor of accompanying numerous jazz icons, from Cab Calloway to Ella Fitzgerald to Sarah Vaughn. Naturally, I fell in love with U.S. jazz and began to frequent such venues as Havana 1900 and Las Vegas, where I jammed with other native musicians who had contracted the same musical virus. It was an extremely beautiful era in which I began to learn about the existence of other musical factors. That is when I played tenor and baritone with the trombonist Jorge Rojas, whose piano-less quartet tried to emulate Gerry Mulligan's instrumental format.

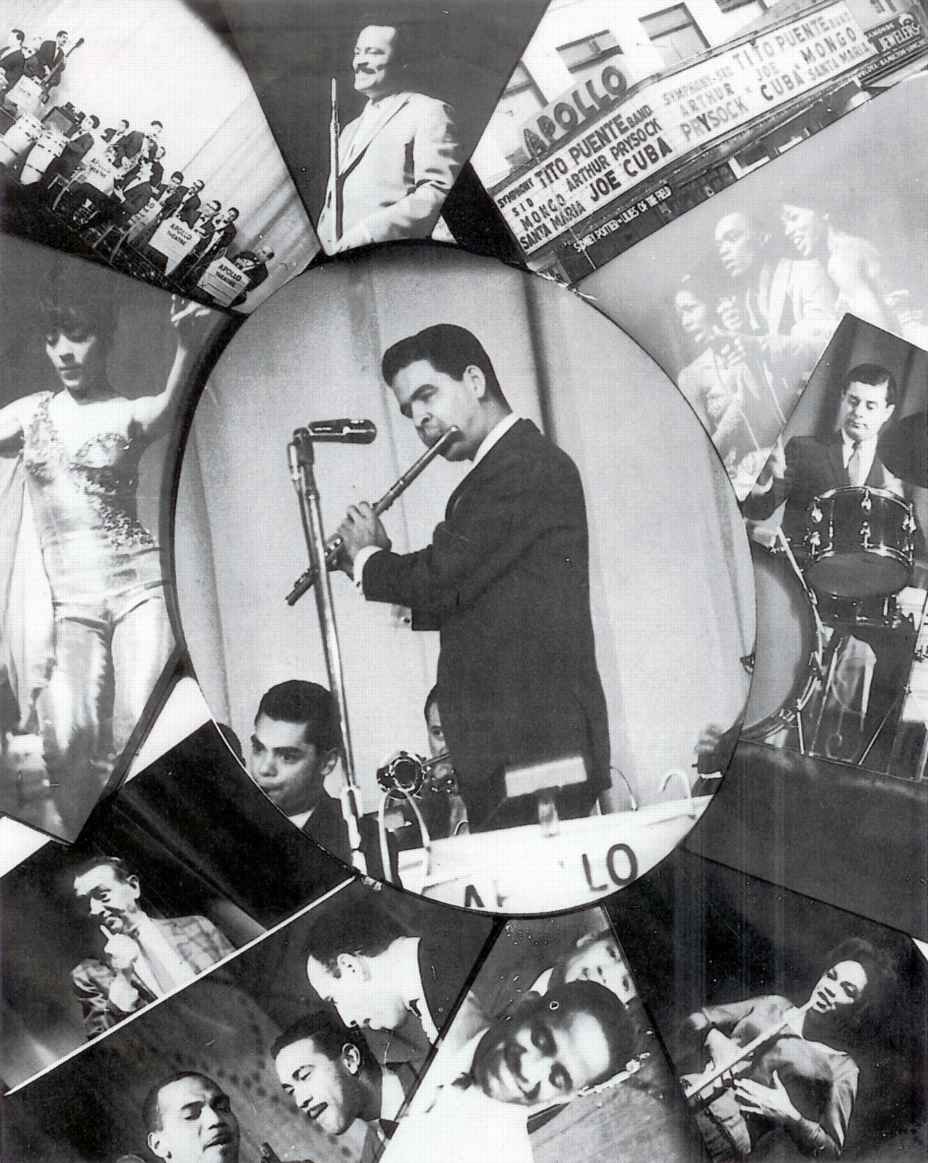

Channel 7 (Rikavision), San Juan, Puerto Rico, 1972. L-R Millito Cruz (sentado), Jesús Caunedo "La Grulla", Mario Ortíz, Bobby Valentín y Rene Hernández. Photographic of Jesús Caunedo.

LT: Eventually, you joined Walfredo de los Reyes' houseband at Hotel Nacional's Casino Parisién.

JC: Yes. Walfredo's band accompanied such singers as Eartha Kitt and Miguelito Valdés. I also worked with Félix Guerrero's band at the Havana Riviera. Guerrero was the mentor of the top Cuban arrangers; he was one of the greatest musicians ever born in Latin America. As a matter of fact, his works are still interpreted by Puerto Rico's Symphonic Orchestra. He was a very humble man, but he had an unbelievable creative capacity. Meanwhile, I participated in various television and radio programs with Ernesto Duarte's band. Duarte and (Guillermo) Álvarez Guedes had joined forces to found Gema Records, and I took part in diverse recordings headlined by such Gema artists as Celeste Mendoza, Rolo Martínez and Rolando Laserie. By 1959, I was working with Rafael Somavilla's outstanding big band at the Havana Hilton. I was basically a tenorist until Somavilla hired me as a last-minute replacement for Tata Palau, who had failed to return from Venezuela. That's when I became definitely embroiled in the alto business. In fact, I ended up playing lead alto with Somavilla and Guerrero in Cuba, and later on with Machito, Tito Puente and every other U.S. band that I was destined to work with.

LT: In the late '50s and early '60s, you had the opportunity to record and perform with the late Arturo "Chico" O'Farrill.

JC: Yes. I was featured in a collaboration between Arturo's big band and the vocal quartet Las D'Aida. I also played in Arturo's last Cuban concert at Havana's Palacio de los Trabajadores. Shortly thereafter, I packed my bags and moved to New York.

LT: In the pre-Castro years, there were many valuable Cuban saxophonists who have been virtually forgotten, despite their important contributions.

JC: Yes, starting with Edilberto Escrich, who earned more money than any other saxophonist in Cuba, while playing with Félix Guerrero's band at the Havana Riviera and recording with practically everyone. Escrich looked a little bit like Johnny Hodges, and was renowned for his beautiful, melodic playing. I also remember the maestro de maestros Bebo Pérez, who played Cuban music in a very lovely manner. Like many other Cuban musicians, he moved to New York in the 1960s. Orquesta Riverside's tenorist, René Ravelo, was admired by his musical peers for his great solos. He is currently residing in Miami, still alive and kicking. Germán Letabard was an incredible technician who had already shown his jazz tendencies in the 1920s. Known for his gorgeous playing, Perro Chino frequently worked as a cirquero (travelling circus musician). He was the first Cuban saxophonist that I saw playing bebop. Tata Palau is ah excellent and sought-after musician who worked for 17 years with Las Vegas' best sax section at the MGM Casino. Tata and I hang out whenever I travel to Miami. Our friendship is older than Methusela's biblical lifespan (LAUGHTER). Gustavo Ms was the tenorist that most younger Cuban sax players, including myself, aimed to imitate at that time. He was our idol, but we never got as close to him as we desired because he was not an approachable person. Pedro Chao was like family to me. We worked together in the housebands at the Havana Hilton and Canal 4 (TV Channel 4). We often consumed freshly baked bread and beer at a Havanese bakery located near the Canal 4 studios. Both Gustavo Ms and Pedro Chao played with Woody Herman's band; Gustavo even did a solo with Herman in a track titled Gus, the Boss.

LT: Is it true that the venerable trumpeter Alfredo "Chocolate" Armenteros was mostly responsible for facilitating your departure from Havana by the end of 1960?

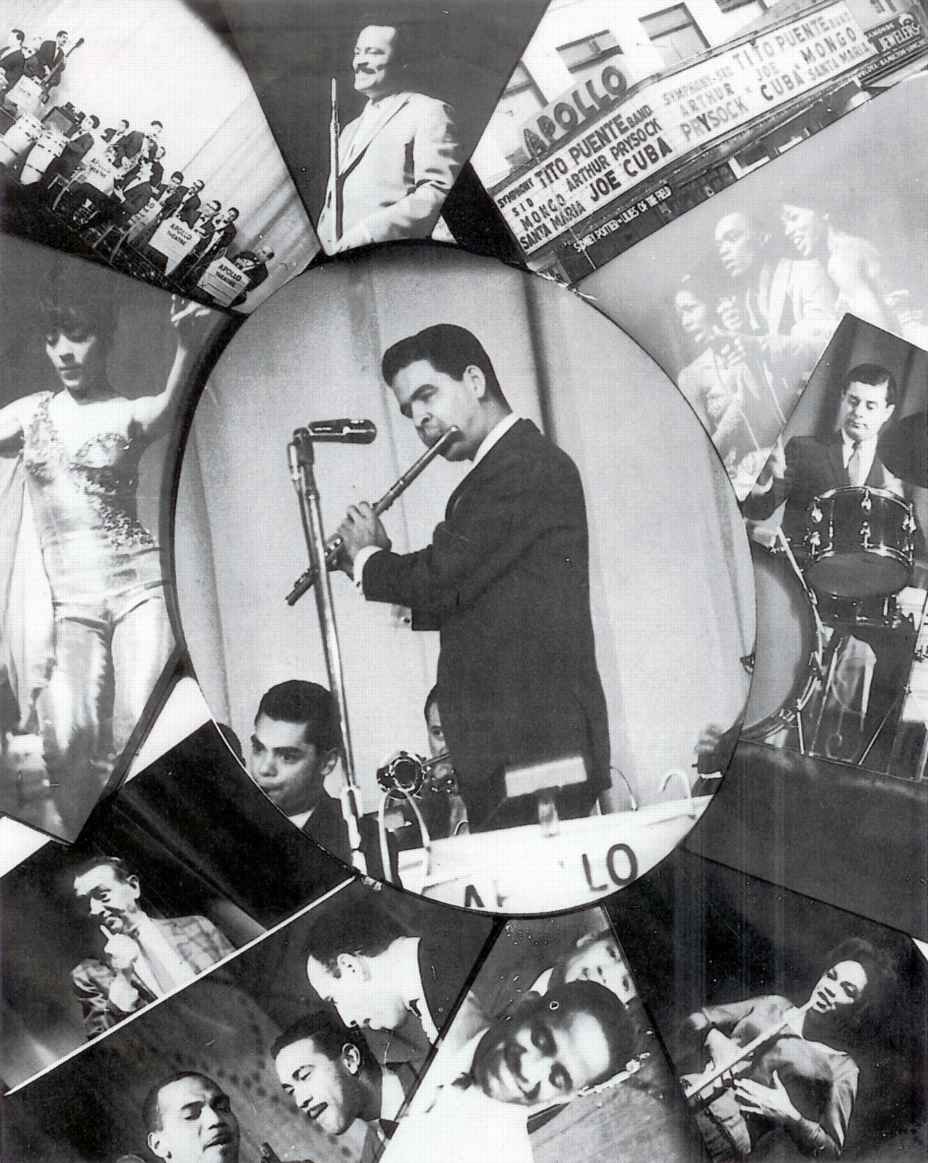

JC: Yes. He produced a phony contract with Machito's orchestra that enabled my wife and I to leave the island and settle in New York, where I did work briefly with Machito (on the LP The Sound of Machito) and became aware of the need to study the flute, which is the last instrument that I learned, after Chocolate referred me to a pertinent instructor, the maestro Alberto Socarrás. In 1961, I left Machito's band and went to work with Emilio de los Reyes at New York's Chateau Madrid and the Catskills. Then I was invited by Julio Gutierrez to travel to Puerto Rico" where I had a marvelous time. After a quarrel with Gutierrez at San Juan's Tropicolo, I packed my suitcases and went back to New York, where I was immediately hired by Tito Puente, to whom I was recommended by Palau. I traveled extensively with Puente to diverse U.S cities (Boston, Washington, Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Diego) and Caribbean countries (Bahamas, Barbados, Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, Venezuela). Working with Puente, from a musical perspective, was a really cool experience. He was a good friend of mine, although my name (or the names of the other sidemen involved) never appeared on any of his album covers.

LT: Was there an after-hours place in New York where the local musicians got together at that time?

JC: Yes. I remember that Julio Gutierrez played at a place called "El Torero," where we jammed after hours. Julio, Chombo Silva and I were the only old-timers. The test of the players were unknown young cats that Julio had brought, for the most part, from Miami: Willy Chirino, Carlos Oliva and Bobby Valentín. I also played at the Apollo, accompanying such stars as Dionne Warwick and Joe Williams, before moving to La Isla del Encanto (The Island of Enchantment) in 1966. My first gig in Puerto Rico involved a quartet at the Dorado Beach Hotel, an exclusive place that attracted multiple millionaires at that time.

LT: How many albums did you record with Tito Rodríguez's band in Puerto Rico?

JC: About five or six, including the one titled 25th Anniversary, which featured a voice-over gimmick designed to pretend that it was recorded in Perú, although it was really recorded in Puerto Rico. Needless to say, such fraud was conducted without our authorization, and we were never monetarily compensated ... I initiated my band-leading career in Puerto Rico at the Caribe Hilton, fronting a quintet that featured Bol Vivar (El Negro's brother) on bass.

LT: Back in those days, you were fortunate to depend on the pianistic support of René Hernández.

JC: That's right. René was one of Cuba's musical glories. He was well known among his professional peers, but never sufficiently recognized by the general public. In 1973, I organized a group to play at Club Luau, a San Juan venue owned by a Cuban named Joaquín Soler. It was a true trabuco (all-star band) comprised of characters such as René Hernández, Bobby Valentín and Camilo Azuquita. Club Luau's became El Condado's descarga epicenter. A year later, I replaced Sacassas as leader of the San Juan Hotel's houseband. This hotel featured such stars as Sammy Davis Jr., Peggy Lee and Nancy Wilson. I was making plenty of money and everything was going marvelously until the local musicians went on strike and ruined everything. Then I went to work for Jimmy Stevens Productions, providing groups of all sizes to the island's hotel conventions. During my 37-year stay in Borinquen, I have recorded with such Puerto Rican musicians as Gilberto Monroig, Lucecita Benítez and José Lugo, among others, while releasing various albums (including Fire and Sugar and Puerto Rican Jazz) as a leader.

COPYRIGHT 2003 Latin Beat Magazine