Released January 20, 2009

Catalino “Tite” Curet Alonso: A Man & His Music

http://www.zondelbarrio.com/Press.php

Aurora Flores

© December 10, 2008

All rights reserved

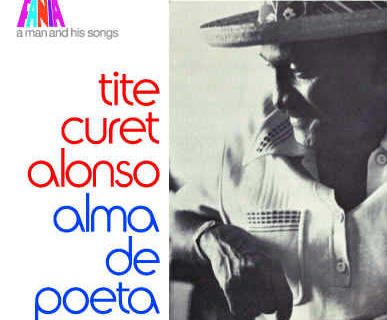

It was in Old San Juan’s “Bombonera” restaurant in 1977 when I

spotted the traditional straw hat and signature daisheke on the man

sitting at the counter. Catalino “Tite” Curet Alonso was holding

a note pad and tape recorder when I sat beside him. He was reserved,

diffident and guarded, until we began talking about Ismael "Maelo"

Rivera’s, “Esto Si Es Lo Mio” that I was reviewing for Billboard

Magazine. That’s when a glint appeared in his eyes, a smile crossed his

face, and we bonded for that moment around talk of ‘Maelo, plena, bomba,

poverty, race, politics, religion y música!

Curet defined a revolutionary period in Latin music. His compositions

brought out the best in the interpreter. Masterworks included Hector

LaVoe’s “Periodico de Ayer” or “Juanito Alimaña,” Cheo

Feliciano’s “Anacaona,” Pete El Conde’s “La Abolición,”

Andy Montañez’ “El Echo de Un Tambor,” Celia Cruz’ “Isadora

Duncan,” and La Lupe’s “La Tirana.”

Curet’s name was ubiquitous, gracing hundreds of album credits of many

of the top Latin music artists of the ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s. He

penned more than 2,000 songs, spawning and jump-starting the artistic

careers of many, from La Lupe, to Cheo Feliciano to Frankie Ruiz. The

most in-demand composer of tropical music, Curet’s songs were guaranteed

hits, and classics today.

“You had to take a number and wait on line,” Ruben Blades told the

L.A. Times when Curet passed away. “His songs could revive any

career, so there was always a fight to get new material from Tite,”

recalled the Panamanian singer/songwriter whose interpretation of

Curet’s “Plantación Adentro” also hit the top of the charts.

Curet helped father the nascent salsa movement that was marking time in

clave through the streets of Puerto Rico and Latin New York. Through

news events, music and lyrics, his words inspired hope and faith, solace

and joy during a time of social upheaval. In more than 2,000 tunes,

Curet was the musical narrator of current events and national pride,

romance and religion. He wrote in a time when the social reality of the

poor was in direct opposition to the political power line, leaving music

as the life-support of hope and faith. Tite Curet reflected the face of

a community in need of answers.

His talent for composing extended beyond the borders of the Caribbean

dipping into Mexico, Venezuela, Paraguay, Spain and Brazil which he

credited for receiving his best musical training referring to them as

the “sorcerers of ‘el medio tono’,” (the half tone). His merengue

for Los Hijos del Rey, “Yo Me Dominicaniso” made much noise while

Tony Croatto’s version of Curet’s “Cucubano” became a hit, later

recorded by Menudo. From Chucho Avellanet to Nelson Ned, Tite Curet

Alonso was a pivotal figure in the musical repertoires of many Latino

superstars.

A compilation of the music of one of Puerto Rico’s most important

composers of the late 20th Century now comes to light after a

fourteen-year absence in Puerto Rico. Emusica has just released a

31-tune double CD set, featuring some of Curet’s most-loved works.

His songs were unavailable since 1995 due to a separate performance

rights society contract Curet signed that built an unnecessary layer of

bureaucracy between the radio stations, the publishing rights

organizations and the composers. Basically, Tite Curet signed a contract

with ACEMLA (Asociación de Compositores y Editores de Música

Latinamericana), a performing rights organization that insisted on

aggressively collecting additional fees from radio stations on top of

the already established publishing rights organizations such as BMI,

ASCAP or SEAC. Now imagine the chaos this would cause if every composer

insisted that every radio station pay another organization, (not even

the individual directly) for performing rights.

“It was a cultural crime,” notes Latin music writer Jaime Torres

Torres of El Nuevo Dia. “An entire generation was deprived of the

genius of this notable and creative songwriter.”

“When a younger generation cannot hear the songs of the masters that

came before them, they create their own,” adds Richie Viera of the

Viera Record Shop in Puerto Rico noting this lack of Curet’s commercial

hits on radio as a contributing factor to the growing trend of

“reggaetón” while salsa music still struggles on the island.

This compilation reflects several of the master composer’s themes.

However, Curet was most proud of his writing skills, in particular his

journalistic ability often pointing to his scant use of adjectives in

crafting a hit number. Tite Curet wrote for newspapers, magazines,

hosted radio shows and was later writing screenplays for stage and

television as well as children’s songs and hymns.

He studied to be a pharmacist but through an uncle who had a print press

he found journalism, writing columns and essays that he later pointed to

as fodder for his musical muse. Curet worked almost all his life for the

U.S. Postal Service, never fully relying on the music business even at

the height of his popularity. He was proud that way. A proud

Afro-Boricua negro, he wrote of his roots on paper and abandoned his

heart to song.

His was a hard life. Born in the pueblo of Guayama, Puerto Rico on

February 26, 1926, Curet’s father taught Spanish and played in the

municipal band of Simon “Pin” Madera. Couples and singles paraded in

plazas across from churches and government steeples where gazebos kept

musicians out of direct sunlight.

However, his parents divorced taking the young Curet to Barrio Obrero.

Those mean streets around the ‘hoods of Tokio, El Fangito, Tras

Talleres and Puerta de Tierra were the last forts of

proletariat resistance while breeding some of the Island’s biggest

talents.

Tito Rodriguez, who later recorded Curet’s hit “Tiemblas,” lived

down the block from the fledging songwriter, as did bandleader Rafael

Cortijo featured on “Se Escapo Un Leon,” on the compilation.

Singer Gilberto Monroig and the internationally renowned composer,

Rafael Hernandez also lived in the neighborhood that spawned much of

salsa’s most genuine artists.

A seasoned man in a time of resistance to societal norms, Curet later

witnessed the worldwide rage against Vietnam and the tsunami of civil

and social change heralded by the ‘60s and ‘70s. This intense,

historical climate shaped Curet’s life and work.

Because his father did not want him to be a musician, Curet studied

music as an adult. When asked for a song, he’d analyze the voice, tone

and timbre of the singer, highlighting the phrasing, diction and

enunciation. His verses were measured and restrained while bursting with

assertive irony, wit and conflict. His study of music theory and

solfegio helped him come up with melodies, lyrical meters and

musical arrangements that augmented the work of arrangers. Artists who

retained him were also subject to his scrutiny, part of the magic and

power included in the creative process of the song.

Curet’s mother was a seamstress but early on she was a voice for the

rights of women. Owing to his mother’s strength of character, Curet was

able to write for women with a sensibility and feminine perspective that

changed the tone of love tunes from wrist cutting torch songs to

empowering odes of self-reliance turning the tables on macho pride way

before Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive” became so popular it was

translated into Spanish.

Just listen to Blanca Rosa Gil belt out her love song of strength in “Fue

Por Mi Bien,” on this compilation. Her voice projects Curet’s words

with such passion you almost feel sorry for the guy she’s breaking up

with. The lush and languid arrangement behind Blanca’s level headed cry

for friendship to replace lost love, puts the composer in the female

psyche of platonic reconciliation while Sophy’s upbeat take of “Amor

y Tentación” is flirty, coy and free-spirited, underlined by a

driving a go-go Brazilian bell. Its message for women was far ahead of

its time

Which brings us to “La Gran Tirana.” This is no shrinking violet

song about I’ll love you no matter how bad you treat me. This is a woman

putting on her “pants” and saying, “When you left me, I hit the

lottery!” Originally written for a male singer, it was Lupe Victoria

Yoli who turned it around into an empowering act of aggression. That

1968 hit sparked Curet’s commercial career and recharged Lupe’s artistic

profession. “Puro Teatro” followed. But it was with vocalist Joe

Quijano’s interpretation of “Efectivamente” where Curet got his

first break in 1965.

Tite Curet’s sympathetic admiration for singer Cheo Feliciano led to his

pivotal role as producer for Cheo’s return to the music scene --–this

time as solo artist instead of singer for Joe Cuba. The subsequent 1971

Fania recording produced five hits including the now standard, “Anacaona.”

Through Cheo, Curet told the folk tale of the valiant Anacaona, a Taino

Indian “Cacica” (chief) from the Dominican Republic who speaks of

a long awaited struggle for her elusive freedom and break from slavery.

Knowing this would be a passionate metaphor for Cheo’s own dependence,

Curet writes “Anacaona” in Cheo’s style making the number his.

Pianist Larry Harlow performs one of the finest solos of his career

accompanied by Oreste Vilato on timbales. The great Louie Ramirez takes

a fluid vibes solo accompanied by Bobby Valentin on bass followed by

Johnny Pacheco’s rhythmic conga drive spearheaded by Johnny Rodriguez’

forcefull bell for a laid-back yet aggressively swinging, history making

session!

Richie Viera who grew up in his father’s record store recalls the many

hours Tite Curet spent in a backroom where he would write his newspaper

column and songs. “Everyday he would come in with a big bag of

plaintain, alcapurrias or bacalaitos. He’d bring enough for everyone

before sitting in the back office at an old typewriter. I’d watch him

write as a line of one song would inspire the beginning of another. He

would throw his head back and begin to sway…”

From the archives of

Roberto Padia

Africanized nationalistic dignity is a recurring theme for Curet who

wrote provocatively on the struggles of a mulatto culture trying to

progress and thrive within an American infrastructure. Pete “El Conde”

Rodriguez said it best in “La Abolición:” the abolition of

slavery does not mean freedom.

Being an occupied nation, Puerto Rico is the subject of many songs of

patriotism and pride. Curet contributed his fair share with the above

numbers including “Mi Musica” and “Profesion Esperanza.”

His words, like knives, cut across the hypocrisy of the times leaving

scars that bear witness today on the injustices that humans commit upon

each other.

Curet expressed his nationalism and politics with pride through the

voice and virtuosity of Puerto Rico’s master-singer, Ismael Rivera. In

the 1975 hit “Caras Lindas,” Curet parades the multi-colored

faces of the various tribes bought over to the Island. He notes their

pain…”Las caras Linda de mi raza prieta. Tienen de llanto, de pena y

dolor.” in verse that cuts across class, gender and race. Like

Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On,” Ismael Rivera tells us what he

sees going on in the different colors of his “beautiful tribal faces.”

Rivera makes “Caras Lindas” an anthem, phrasing verses in his

rhythmic vocal style accompanied by an arrangement sampling “blues

riffs” on the trombones. Tugging back on notes that eventually join

Mario Hernandez’ tres, voice and strings together solo in unison as if

crossing over into La Perla on Christmas morning where Lotus Flowers

also grow in the muddy waters of destitution.

From “Caras Lindas” to Cortijo’s classic plena “Se Escapo un

Leon,” the pride shines through in these Boricua spotlights of

musical stories. “El Eco de Un Tambor,” “Pan de Negro,” and “Mesie

Bombe,” all talk to Africanized themes in salsa with a rhythm, tone

and cadence-suggesting poet Luis Pales Matos.

Curet combats the social issues of his time with lyrical laments within

a dance format. An actual story, friends Rafael Viera and

Franklin Hernandez introduce singer and musician Billy Concepción to

Curet in a restaurant. Concepción was blacklisted by the music industry

and couldn’t find work. A father of six, he recounts the overwhelming

feeling of having the world on his shoulders. Curet immediately took his

pen and wrote “Lamento de Concepción” on a napkin. “Concepción

eleva la vista al cielo. Va gritando hay niños que mantener.”

expressing the universal feeling of impotence at not being able to

support the family.

Billy Concepción did leave P.R, for New York rescued by Cortijo who took

him on tour. Roberto Roena’s take on this tune has a deceiving funk and

danceable swing, with a biting back beat on congas by Papo Pepin,

sandwiched between pastoral samba passages that betray its tragic tale.

“Galera Tes” is a story of injustice behind the justice system.

Built in the ‘30s in rejection of Spain’s penal system, Puerto Rico’s

infamous penitentiary, Oso Blanco (White Bear) was a hotbed of

controversy by the ‘70s spinning off groups like the ñetas in

retaliation to inmate abuse. A young Ismael Miranda gets his street

‘cred in this protest song against prison violence. “Galera Tres”

first appears in a Marvin Santiago recording without Curet’s name. The

composer deliberately credited Santiago’s wife enabling her to receive

royalties while Marvin was incarcerated.

Curet wrote many songs celebrating life, drums and music. “Evelio y

la Rumba” becomes part of this collection joining other tunes such

as “El Primer Montuno,” here interpreted by the Andy Harlow band.

“La Esencia del Guaguanco,” as expressed by the Willie Rosario

orchestra rejoices in the essence of this Cuban rhythm.

Curet’s religious compositions embrace “Tengo El Idde,” (I have

protection), with Celia Cruz and Johnny Pacheco warning haters about

their spiritual shield, Curet’s words reflect the sacred rituals of poor

communities. Ray Barretto’s rendition of “El Hijo de Obatala” on

the other hand was so compelling many believed Barretto was a

practitioner of the faith. What’s even rarer on this production is a

young Tito Allen masterfully vocalizing with Hector LaVoe doing second

and Meñique doing first voice on the ‘coros.’

In romance, Curet is at once jilted, as in “Periodico de Ayer”

sung by Hector LaVoe, as he is vengeful in “Aquella Mujer”

interpreted by Bobby Valentin. Even "Piraña" rages against yet

another wonton woman reviled yet desired. Just as quickly as he condemns

the female sex, Curet writes the lusty “Las Mujeres son de la Azucar”

recorded by Sonora Ponceña.

In this second CD the romantic theme is distributed between these

giants: Cheo Feliciano, Vitin Aviles, Ismael Miranda and Santos Colon

among the many. Cheo brings us the ballad, “Enfriamiento Pasional”

complete with a string ensemble and muted brass to mourn the loss of a

passionate affair. Vitin Aviles brings us a dark love song of emotional

blackmail in “Temes,” interpreted in the orchestrated style of

Tito Rodriguez. Ismael Miranda’s bolero “Ayer Me Entere” displays

a tight Orq. Harlow accompanying the young vocalist who is dismissing an

ex as nothing more than an adventure. Bandleader Tommy Olivencia’s “Como

Novela de Amor” is another crafty bolero where a woman’s love is

categorized as merely a soap opera. This bolero is interesting because

it starts with the masculine tenor crooning of José “Pepe” Sanchez and

then bumps up the pace and turns the singer around bringing in the crisp

soneos of Chamaco Ramirez to finish the piece…¡Que Cheveron!

Roberto Yanes’ balada rendition of Curet’s “Ante la Ley”

was a bold move for the Fania International label back then. At the top

of their game in what they had popularized as “salsa,” Masucci began to

record pop artists. He enlisted C. Curet Alonso to compose this tune.

Santos Colon rounds out the bolero series with his version of “Fiel,”

complete with a lush orchestration featuring horns and oboes around the

theme of loyalty.

In his later years, Tite Curet Alonso left Puerto Rico to be with family

in Baltimore, Maryland. On August 5, 2003 he died of a heart attack. He

was 77. The Institute of Puerto Rican Culture gave him a hero’s wake. He

was buried in Santa Maria Magdalena de Pazzis Cemetery in San Juan.

Ruben Blades suspended his “Farewell Tour” to attend the funeral. Cheo

Feliciano, one of his closest friends served as one of many pallbearers.

It was said that like the Island’s native tree frog, el coqui, Tite

Curet Alonso died when he could no longer feel the warmth of his beloved

little island.

© December 10, 2008

All rights reserved